I was VITAL faculty

By: Carrie Diaz Eaton, Associate Professor of Digital and Computational Studies, Bates College, @mathprofcarrie

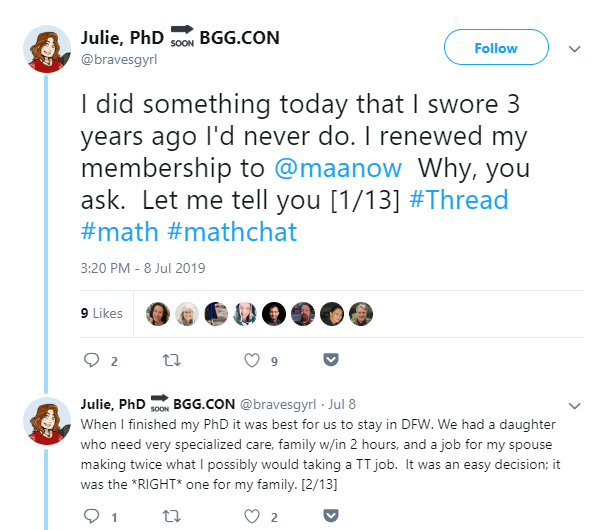

See entire thread at https://twitter.com/bravesgyrl/status/1148356206290984960

Dr. Sutton (@bravesgyrl) wrote an amazing series of Twitter posts this summer.

She talked about how it feels to be a non-tenure track faculty member, mingling in our broader professional world. She talked about Dr. Levy’s work in reframing nationally and personally the work of non-tenure track faculty into VITAL faculty. Reading it inspired me to reflect on a little of my own experience.

Are VITAL placements a first choice or a second tier consolation prize?

I am posting the framing question early because I want to jump right to the heart of the misunderstandings in our community.

Carrie Diaz Eaton, 2010, in her first year teaching at Unity College, a small environmental college in Maine. Photo Credit: Mark Tardiff

First, let us establish the broad variation of VITAL faculty positions. They range from adjunct positions without benefits to full-time positions with benefits. Full-time positions can be for short non-renewable contracts, such as visiting positions, postdoctoral positions, and full-time temporary positions. They can also include positions with a long-term guarantee of employment and promotion. This means titles for VITAL faculty can range from Graduate Teaching Assistant and Visiting Professor to Associate Professor of Practice, Senior Lecturer and Full Professor. At some universities and colleges, these positions make up a small percentage, at some they make up 100%.

In Maine, where I live, the majority of higher education institutions are non-tenure institutions and there are no R1 math institutions (the flagship university has a Master’s program only). My husband started as a lab instructor at Maine Maritime Academy and then moved into a non-tenured, but ranked position with half-time research responsibility on soft-money. Eventually, he moved into a full-time research Assistant Professor of Chemical Engineering position at the University of Maine, fully soft-money funded by his own grants. When I was in graduate school, I adjuncted for Eastern Maine Community College as part of a workforce development contract - I taught a class for new hires at Jackson Laboratories that needed laboratory math skills. At College of the Atlantic, I was Visiting Faculty as I filled in for a colleague on sabbatical until the birth of my daughter. At Unity, I was in a ranked, non-tenured position and was promoted to Associate Professor of Mathematics in 2013. Each of these positions described above were what we would term “non-tenure track,” but are VITAL positions. In fact, if you include my graduate teaching assistantship, between the two of us, we will have held pretty much every type of VITAL position.

So for us, were these positions a choice or a consolation prize? The answer is “it was a choice, but it was also complicated.” I’m going to guess that this answer will ring true for many others as well.

Penalties, priorities, and positions

Why were we in these VITAL positions? Geographically constrained searches often result in VITAL placements. This can be for two-body problems or other reasons why someone might want to geographically constrain one’s search. We decided to start searching exclusively in Maine because I had one small child and wanted to be closer to family support. By this time all of our parents lived in Central-Northern Maine. We also had additional constraints. In our rurally-constrained search area, math teachers are often needed, but engineering teachers and practitioners are not. So finding any full-time position for my husband in Maine seemed like we had hit the jackpot and it didn’t matter whether it was tenure-track or not. I also want to point out that VITAL colleagues often have less privileged backgrounds, and I won’t get into the reasons why here, but it was true also for us, and I consider it a factor in our trajectories.

We moved my family so that my husband could accept his full-time VITAL offer. We were happy to settle close to family and to contribute back to what had become our home state. My part-time visiting VITAL position was a good balance for me to keep doing the teaching I loved while devoting my primary time to research, my toddler, and incubating my new baby. When I was ready to return to full-time, I had an opportunity to accept a postdoctoral position in Maine to continue a tenure-track trajectory, and I choose the VITAL assistant professor job instead. Why? I felt a ranked position at a non-tenure school offered more stability. I was also ready to take a break from research pressure as much as possible and focus on my family and my teaching, which had always been my first passion.

Stereotypes, snobbery, and storytelling

In none of the above did I ever say my husband and I were bad at research or teaching and that is why we landed in non-tenure track positions. We just had constraints about which we tried to maximize our objective function and we made choices that fit our desired lifestyle the best we could. But I was still met with less enthusiasm when I would explain I was a non-tenure track. In fact, I was actively shunned by researchers in mathematics with which I had common research interests.

It is true that it can be slow and difficult collaborating with faculty at institutions like mine and my husband’s. It was hard to do research while teaching a 4-3 course load that did not pay enough to cover summer childcare. It was hard to get that first grant when I was ready to get back in the game because we had no grants office. But I found a broader community and that made the difference. I had colleagues at the nearby research university in Marine Science that helped me learn the process of grant submission at NSF. I had colleagues from graduate school, now at positions at elite colleges, that would let me couch surf so that I could afford to go to a professional society conference. In many ways, I worked so much harder than I do now with extra resources at my disposal. That should mean that my accomplishments are weighted even more because I did them despite the challenges of being a VITAL faculty member. But I don’t think that is the storyline that plays in our heads when we see our VITAL faculty in our research and teaching spaces. Anecdotally - nothing about me has changed, but since I’ve moved into a non-VITAL position, I’ve received more invitations to author, more invitations to co-edit, and more invitations to speak. Perhaps this just indicates a broader personal trajectory, but I can’t help but see the stark difference this past year.

How can we change the narratives we’ve created about VITAL faculty? We can recognize our resources and position and use them to help advance the goals of our VITAL colleagues. We can create storylines that appreciate the challenges of VITAL faculty, appreciate their intellectual contributions, and raise them up as crucial parts of our community. Lastly, we have to work harder to fully accept the richness of our diverse MAA ecosystem on all axes and nurture it to be even stronger and more resilient.