Testimonios: Dr. Stephan Ramon Garcia

Testimonios, a new publication from MAA/AMS, brings together first-person narratives from the vibrant, diverse, and complex Latinx and Hispanic mathematical community. Starting with childhood and family, the authors recount their own particular stories, highlighting their upbringing, education, and career paths. Testimonios seeks to inspire the next generation of Latinx and Hispanic mathematicians by featuring the stories of people like them, holding a mirror up to our own community.

The entire collection of 27 testimonios is available for purchase at the AMS Bookstore. MAA members can access a complimentary e-book in their Member Library. AMS members can access a complimentary e-book at the AMS Bookstore. Thanks to the MAA and AMS, we reproduce one chapter per month on Math Values to better understand and celebrate the diversity of our mathematical community with folks who are not MAA members.

Dr. Stephan Ramon Garcia

According to certain metrics, I am a highly successful mathematician. In 2019, I was elected a Fellow of the American Mathematical Society and was awarded the inaugural AMS Dolciani Prize for Excellence in Research. I have been on the editorial boards of well-known journals and written over a hundred papers, along with several books with top publishers. I have an endowed professorship at a top-tier liberal arts college, and I have received multiple NSF grants and six teaching awards. So it would seem that I know what I’m doing. However, I was rather clueless for much of my journey and often muddled through without clear direction. Nothing about my career was inevitable: some favorable circumstances, fortuitous timing, coincidences, and good luck played important roles, along with lots of hard work.

Early Life

My father’s family fled to the United States from Cuba in 1960. They had to quickly adapt to life in Miami. My grandfather worked as a Spanish teacher and my grandmother as a hairdresser. My father studied at Miami-Dade Jr. College and earned an associate degree in electronics.

My paternal grandparents, and my father and aunt (Cuba, 1950s).

My mother was born in Hiroshima during WWII and is an atomic bomb survivor. She attended some college in Japan but did not complete her English degree. In 1969, she was visiting her sister, who had married a U.S. marine, in New Jersey. My parents were set up on a blind date and the rest, as they say, is history.

My maternal grandparents (Japan, 1946).

Our new neighborhood was lower middle-class, with cars propped up on blocks in driveways and frequent petty crime. The nearby public schools were mediocre, which caused my parents to enroll me in a series of private schools. I was an only child and my parents were frugal, so this was just barely affordable. I recall little about my first few schools, save for a vague sense that I did not belong there.

From third to fifth grades, I attended the local public elementary school. My third-grade teacher gave me more advanced math books, and I started learning algebra and geometry. I was placed in a special program for “gifted and talented’’ students and bussed once a week to another school for enrichment activities.

We moved to a different neighborhood when I was in the middle of fifth grade. Although the public schools there were much more highly rated, it was at first a step back for me. Instead of being viewed as “gifted,’’ as I was in my old neighborhood, I was largely overlooked, even being placed in the lowest English class. Being one of the few Latinx students in the school, I stuck out and was frequently picked on. Fortunately, I moved to middle school after a few months, which was a welcome reset. There I was a good, but unexceptional student in everything but science (I was awarded the prize for best science student at my middle-school graduation).

My high-school career was unremarkable. I was the only Latinx student in most of my classes. I did not know how to learn although I was adept at going through the motions. Although I received a 5 on the AP Calculus BC examination,1 I did not truly understand calculus. I simply knew how to robotically perform computations.

The Garcia family in the 1970s. Seated are my paternal grandparents and I. My parents stand at the upper right. My aunt and her husband stand at left.

My parents were immigrants with little knowledge of higher education in the United States, and we did not know how to “play the game’’ of college admissions. It was natural for us to assume that good grades and test scores were the keys to success. Now that I work at an elite private college, it is clear to me that admissions committees look at much more than grades and test scores. Students are often so “well rounded’’ that they can appear nearly spherical and paradoxically featureless.

I had no curiosity or desire to attend school outside of California, and I applied only to large universities in state. We knew nothing about small liberal arts colleges.2 I did not get into Stanford, despite excellent grades and test scores. I was simply not “well rounded’’ in the way that admissions committees valued. I had no student-government experience or athletic achievements; I started no clubs, performed no volunteer work, starred in no plays, and gave no solo concerts.

Fortunately, my grades and SAT scores were high enough for me to gain admission to UC Berkeley with a UC Regents Scholarship. Berkeley was only an hour from home, so I never considered any of the other schools to which I was admitted.

Undergraduate Education

I had no idea what to do at UC Berkeley. There was no internet to speak of: no course reviews or “frequently asked questions’’ pages were available. I simply signed up for classes that roughly mirrored my high-school schedule. It seemed natural for me to take English, history, math, and science. Nobody told me to do otherwise.

Early on, I got the top score on an exam in a 500-student mathematics class. Although there was no sign that the professor paid any attention to me or my performance, this was my first genuinely positive mathematical experience since elementary school. Brimming with confidence, I received a middling score on the second exam, although I did get an A in the end.

Overall my work ethic as an undergraduate was poor. I spent most of my time playing video games or Dungeons & Dragons, practicing guitar, or playing basketball. I did as little work as possible while still earning a decent grade. Instructors did not notice or care that I skipped class frequently. In a “small’’ 100-student class, who would notice my absence? Certainly nobody ever reached out to me about it.

By my sophomore year, I was leaning toward being an English major. I did not realize this at the time, but it was my burgeoning competence in mathematics that made me effective in my English courses. Essays and proofs are not so different: in both cases one makes a logical argument, supported by facts (either quotations from the text or previous results), intended to convince the reader that the thesis is correct. However, I quickly grew disillusioned with the English major. The books that my instructors selected felt increasingly motivated by cutting-edge literary fashion (which I did not care for), and I felt that I was being rewarded for inventing interpretations of texts that, in my heart, I knew that the author did not intend.

In the absence of advising, I continued my old “high-school schedule’’ although I dropped English courses in favor of history and music. All the while, I was taking physics and mathematics (I eventually realized that what I liked about physics was the mathematics). As I progressed through linear algebra and differential equations, I developed a genuine interest in mathematics. I started reading popular titles like Infinity and the Mind; Gödel, Escher, Bach; and The Man Who Knew Infinity.

My initiation into proof-based, upper-level courses was a shock. I took abstract algebra and real analysis first because these courses were labelled the lowest of the upper-level courses: 104 and 113, respectively. My abstract algebra professor was an unenthusiastic postdoc who lectured out of the book; the 8 am time slot ensured that I did not attend often. On the other hand, my instructor for real analysis was spirited and engaging. I would lean toward analysis and away from algebra for several years because of these experiences. This experience highlights an important lesson for students: a good professor can make any topic interesting and a bad professor can make any topic uninteresting. Don’t judge a topic based upon one course!

Mathematics, in which the grades depended entirely on homework sets and exams, proved to be a good match for my largely nocturnal existence. There were no labs or discussion sections, and professors did not seem to complain so long as my assignments were turned in and I showed up for examinations. In retrospect, perhaps I was turned off by the posturing and preening of some of the other students.

I briefly attended the Putnam3 seminar, but did not find the atmosphere inviting. The professor in charge had a gruff demeanor and talked mainly to a few international students, all of whom seemed to have had previous math-contest training. I decided that the Putnam was not for me (or perhaps it was decided for me).

Being of mixed race ensured that finding community was difficult. It forced me to be independent in a sink-or-swim fashion. It never occurred to me to want role models who were like me. From what I could tell, there were no people like me. Fortunately, these feelings never hampered me academically. It just seemed natural, indeed obvious, that I would be different from other students and my instructors. This probably helped me navigate a large, impersonal place like UC Berkeley

Since I had spent so long settling on a major, I needed to double- or triple-up on mathematics courses in order to graduate (it took me five years). I did well in most classes, stood out in a few, and was mediocre in some others. In particular, I earned top marks in a graduate-level analysis class, which proved fortuitous since the professor later served on the graduate admissions committee when I applied.

Soon my senior (technically fifth) year loomed on the horizon. I wanted to avoid the real world; getting up early in the morning and wearing a tie sounded dreadful. So I applied to graduate school.4 I had no idea what being a professor was like, nor did I know anything about research in mathematics. I liked mathematics and was intrigued by it, but I hardly knew what being a mathematician meant.

I recall one conversation with a professor. He told me not to apply to top-tier places on the East Coast. He explained that Princeton, Harvard, MIT, and the like were out of reach since I had only taken two graduate-level courses, and I was neither a Putnam Fellow nor an International Mathematical Olympiad medalist. So I applied only to a few schools in California. My performance on the GRE, overall good grades, and the Berkeley name, ensured that I made it to the next stage.

Graduate Education

I was accepted by every graduate program to which I applied, although that is hardly an accomplishment since I applied only to a handful of schools in California. I had some satisfaction in rejecting Stanford’s offer; they had rejected me as an undergraduate. In retrospect, I might have benefited from their smaller program. However, at the time the mathematics PhD program at Berkeley was tied for number one in the nation, so I did not seriously contemplate leaving for slightly lower-ranked Stanford. After all, Berkeley was familiar and Stanford seemed so distant.

There were ten of us assigned to two adjoining offices in the windowless corridors of Evans Hall. Of these, I think only two or three of us completed the program; at least five quit or were kicked out. There were a few other Latinx graduate students in the department, but they all seemed to have been the top students in their countries and many had experience in the International Mathematical Olympiad.

Because I already had a circle of friends in Bay Area, I did not hang out in the math department. Consequently, I did not learn useful tips from other graduate students or from postdocs and professors. Since I did not understand the titles or abstracts, I did not attend colloquia or seminars. I failed to integrate myself into the social side of mathematics. I simply had no idea how mathematicians socialized or learned. The department at Berkeley was large, and it was possible to disappear completely, which I did. Nobody told me what I needed to be doing, and I got lost.

Because I had an NSF Fellowship, I did not need to teach. However, I asked if I could teach one course per semester. It seemed like a good idea to have teaching experience since, I imagined, teaching was an important part of being a professor. I went on to win several teaching awards at UC Berkeley, which opened a few doors.

The transition from taking classes to doing research was left largely unexplained. Since I liked analysis and had just taken complex analysis with Donald Sarason, I asked him to be my advisor. He agreed without hesitation. Because of my lackluster performance in the program and my sparse attendance at department events, I suspect that many other potential advisors would have politely excused themselves

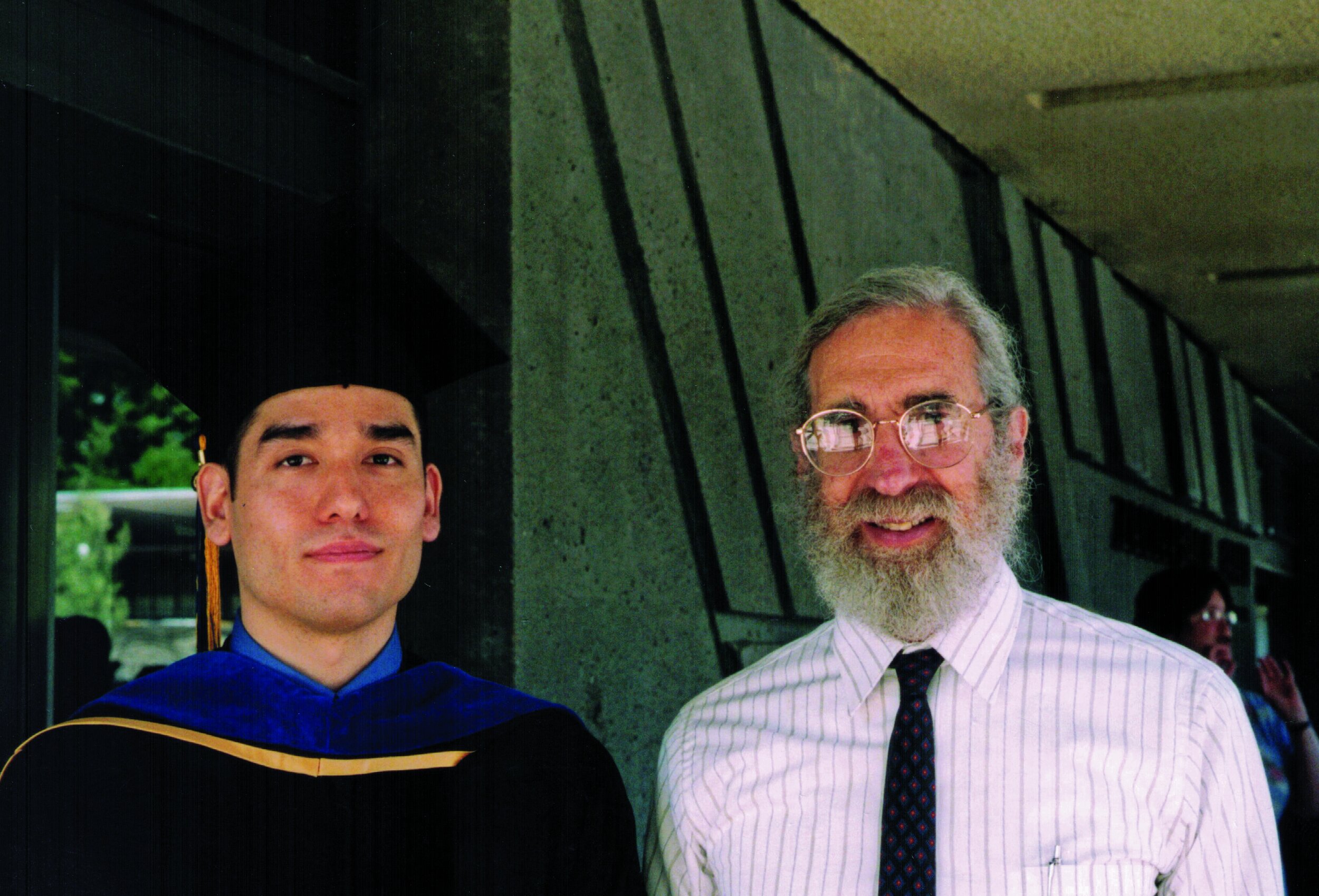

With my thesis advisor, Donald Sarason, at my graduation from the PhD program (2003).

Sarason, then nearing seventy years old, was kind and patient, but unusually quiet. His advisor, Paul Halmos, said “[he] is a quiet man; he never uses eight words when seven will do.’’ Perhaps a more astute career move would have been to attach myself to an up-and-coming star, swimming in grant money and fresh off an International Congress of Mathematicians (ICM) lecture or major prize. However, the preening roosters and showoffs were attracted to such advisors, and it is not clear that I could have flourished in such a competitive environment. Somehow things worked out for the best.

My qualifying examination committee consisted of Sarason, Michael Christ, and Vera Serganova, along with an engineering professor who admitted sheepishly that he was just there as an outside observer. Although I answered the first few questions well enough, things turned for the worse. Christ is a tall, imposing man with a deep voice, and I felt somewhat intimidated when I fumbled one question. Serganova asked a few algebra questions in a kindly fashion, perhaps taking pity upon me, or possibly just throwing out softballs since algebra was the minor topic on my examination. After a long several minutes in the hallway, I was informed that I had passed, although I certainly felt that I hadn’t or shouldn’t.

My fifth year of graduate school rolled around, and I had accomplished relatively little. Without formal coursework or well-defined goals, I had spent most of my time in graduate school on non-academic endeavors, although I had apparently done just enough to convince the department that I was worth keeping around. Probably I could have used a swift kick in the rear or stern words from some authority figure.

I had no idea how to be a mathematician, no idea how to do research. I had never been to a conference, nor had I met key players in my field. By some stroke of luck or inspiration, I managed to put together a decent thesis. Although my dissertation solved a problem from an old Bulletin of the AMS article, it was written so abstrusely and tersely that it gained little traction. I briefly met one of the authors of the Bulletin article at my advisor’s seventieth-birthday conference. However, I could not succinctly express my ideas: I was a poor mathematical communicator. The professor appeared impatient with my rambling, and I received a cool and critical response. Clearly, I had no idea how to give an elevator pitch.

Sheldon Axler probably saved my professional career. As a clueless graduate student just about to hit the academic job market, I needed letters of recommendation. But I didn’t know anyone! Sarason reached out to his former student, who was, fortunately, willing to meet with me. I traveled to San Francisco State University, where Axler had relocated as department chair after a distinguished career at Michigan State. Fortunately, he entertained my rambling and incoherent explanations long enough to see that there was something worthwhile behind the nonsense. He wrote a letter for me which, I can only assume, was a decent one.

I had survived graduate school, if only barely. A last-minute thesis breakthrough and my advisor’s connections had saved the day. What next?

After Graduate School

I was fortunate enough to obtain a postdoctoral position at UC Santa Barbara. My girlfriend, Gizem Karaali, completed her PhD at UC Berkeley the following year and also secured a position at UCSB. We married soon after.

My mentor at UCSB was Mihai Putinar. Although the graduate students dreaded him as the “demanding Eastern European analysis professor,’’ I found him to be a prolific mathematician with a broad perspective. He gave timely advice about mathematical politics, grant writing, and all aspects of the profession. We wrote several influential papers during those years and I really came into my own as a mathematician. I probably would not have succeeded without Mihai’s guidance.

With my mother (left), paternal grandparents (middle), and Gizem (right) at my graduation from the PhD program (2003).

Our daughter with her great grandparents in Miami (2010).

Although I spent most of my time on research, I won another two teaching awards at UCSB.5 Moreover, I turned my bad habits around and became a workaholic: it was the only way to survive the publish-or-perish academic job market. Now that I knew what I was doing, there was a lot of catching up to do! Moreover, I felt that I had to work twice as hard for half the recognition: I was not in a “hot area’’ at the cutting edge of fashion, and I had to struggle against the constant perception that I was not a “real’’ mathematician and just there for window dressing.

The economy was still humming in 2005, with the Great Recession several years away. Gizem and I were fortunate that hundreds of tenure-track positions were advertised that year; we each applied to over one hundred. It strikes me even today how one’s career opportunities depend upon the vagaries of fate. We had several pairs of job offers, along with multiple single offers. We were in a strong position with plenty of bargaining power. Would we be mathematicians today if we had applied in 2008? Perhaps not.

Looking Forward; Some Advice

As a Cuban-Japanese person from New Jersey, my life story is hardly universal. Nevertheless, I think that we can still identify some counterproductive behaviors, unfortunate incidents, and repeated mistakes from which we can extrapolate some useful general recommendations.

First of all, don’t let other people limit your options. Don’t let people tell you what you are capable of, set your limits, or deny you opportunities. You can be your own best advocate: if you don’t believe in yourself, others are unlikely to step up and go to bat for you.

Second, get your head out of the sand. Meet people and socialize: mathematics is a social endeavor. Don’t be afraid to ask questions; if you don’t ask, you won’t find out the answer. Learn from other people and network, network, network! There are lots of things that “everyone knows,’’ but nobody tells you. If you isolate yourself, then you won’t learn the ropes and you’ll get left behind.

Lastly, focus and work hard. The first stages of one’s mathematical career are difficult and stressful; for someone swimming upstream doubly so. Whatever you do, put in 111% (since you’ll have to outwork those 110% folks). Sometimes you will have to do more work for less recognition. You’ll eventually earn your place at the big table and then you can pay it forward and lift up the people behind you.

Although I’ve done a bunch of things over the years, I believe that my biggest impact has been in the classroom. Students look to you as a role model and mentor, but more importantly they look to you as the one-stop shop for part-time jobs in the department, research opportunities, graduate school advice, letters of recommendation, and emotional support. You are the one who needs to tell them the things that “everyone knows.’’ You are the one who needs to ensure that they don’t make the same mistakes that you did. Once you figure something out about how the world works, make sure your students know!

I mentioned times when teachers thought lower of me because of my background or when professors, perhaps inadvertently, dissuaded me from pursuing opportunities. I still occasionally find myself in settings that are uninviting, in which people view me as necessary decoration, a nod to diversity. You just have to prove people wrong. Once you get to the big table, don’t be afraid to stand up for yourself or voice your opinions. Most importantly, find like-minded individuals and mentors. Others have been there before you, so make sure to draw upon their collective wisdom!

Receiving the inaugural AMS Dolciani Research Prize at the 2019 JMM.

Although my “success’’ was not pre-ordained, I did have some lucky breaks. I was fortunate to have parents who valued education and a stable home environment. Both of my parents overcame poverty and suffering; I benefited from the opportunities they struggled to give me. The Berkeley stamps on my diplomas carried significant weight at crucial moments. My advisor’s connections gave me a last-minute reprieve when I needed another letter of reference. At UCSB, I found exactly the right mentor at the right time. Moreover, the global economy cooperated with our job searches.

Even though I now have many of the trappings of “success,’’ my journey was neither inevitable nor without difficulty. There were moments of indecision, self-doubt, and discouragement. I hope that students reading this will realize that even those who seem to know what they are doing may have once been lost themselves.

1From collegeboard.org: The AP Calculus BC Exam will test your understanding of the mathematical concepts covered in the course units, as well as your ability to determine the proper formulas and procedures to use to solve problems and communicate your work with the correct notations. According to the College Board a 3 is ‘qualified,’ a 4 ‘well qualified,’ and a 5 ‘extremely well qualified.

2Years later, when my parents moved out of my childhood home, I found recruitment letters from Pomona and Harvey Mudd. None of us knew at the time that I would end up in Claremont.

3From the Mathematical Association of America website: The William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition is the preeminent mathematics competition for undergraduate college students around the world.

4 In hindsight, this was a good idea. I graduated in 1997, as the tech industry was booming. Many of my friends went into industry, only to be laid off or have the startups they worked for go belly up with the burst of the dot-com bubble in 2000. It took some time for them to find their feet again, only to get wiped out again by the 2008 crash.

5 Upon my arrival at UCSB, one of the senior faculty members advised me “don’t spend too much time on teaching. You are here to do research.’’ Because I had won two teaching awards at UC Berkeley, there was apparently some fear that I was not serious about research.